THE HUMAN TOUCH

From community engagement to inclusive planning, sustainable cities must be shaped by and designed for the people who live in them. Speakers from Sustainable Cities in Action Forum 2024 share their perspectives

Why else are we doing this if not for the improvement of people’s lives?

Gordon Gill, Founding Partner of Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture

Architect Gordon Gill notes that, whether directly or indirectly, the ultimate goal of any sustainability intervention is human wellbeing and livelihoods

In 1904 Scottish biologist and sociologist Patrick Geddes proclaimed: “A city is more than a place in space; it is a drama in time.”

Today, more than a century on, 4.4 billion people (and rising), some 56 per cent of the world’s population, are playing leading roles in that drama as they experience the effects of our warming climate; no more so than in countries of the global south.

The tools available for urban climate resilience are manifold, from cutting-edge technology such as digital twins, to low-tech interventions that leverage local adaptive techniques. Yet as cities explore ways to mitigate and adapt to weather events and rising temperatures, there is one constant: the need to place people front and centre in urban processes.

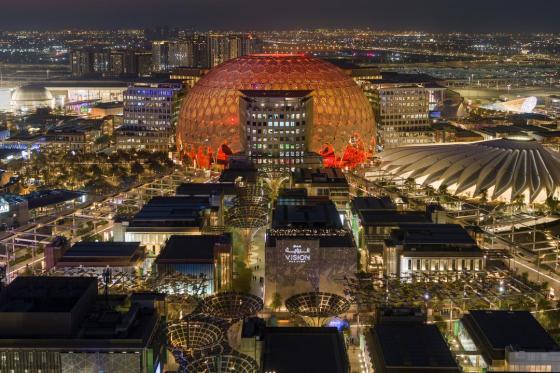

That was the consensus at Sustainable Cities in Action Forum 2024, which, on 4-5 March, convened more than 400 urban leaders and experts from across MEASA and beyond at Expo City Dubai. As Gordon Gill, Founding Partner of Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture, noted: “Why else are we doing this if not for the improvement of people’s lives?”

Happily, there is a direct interplay between interventions that seek to protect and restore our planet and those that target social and socio-economic sustainability.

Women and the city

In her seminal book ‘Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men’, Caroline Criado-Perez explores the ways in which traditionally ‘male’ city planning excludes women and girls. That includes public transport routes that fail to accommodate women’s travel patterns (school drop-offs, suburban commutes) and safety concerns (insufficient street lighting, absence of CCTV in secluded zones).

Sophia Schuff, Director and Team Lead at urban research and design consultancy Gehl, adds public health to that list. Citing “the double burden of disease”, which sees women more vulnerable to infectious and non-communicable illnesses, she suggests that sustainable, gender-responsive city planning can mitigate that risk.

Using 15-minute cities as an example, Schuff says that while walkability reduces the number of car journeys, cutting emissions, facilitation of more active lifestyles also minimises the occurrence of non-communicable diseases by which women are disproportionately affected.

Moreover, she adds, there is an intersectional effect. “We're not only getting women out walking, we're giving them access to nature, which is also incredibly important. In pregnancy. For example, every five minutes that a pregnant woman is exposed to nature is five minutes that actively improves the health of a child in utero.”

Child’s play

Gehl takes an ethnographic approach to sustainable placemaking, observing community behaviour in situ and using data gathered to inform interventions.

Schuff describes a project with Abu Dhabi’s Early Childhood Authority (ECA), which sought to encourage children to spend more time in outdoor physical activity.

In one neighbourhood studied, she says, there was a children’s playground that was barely used. “The kids didn’t like it and the nannies didn’t take them. Over the course of a day’s observation, we counted maybe 10-12 children.

After observing children’s and carers’ behaviours at the playground, the team took its findings to the ECA. And following discussions with different local entities including a major regional developer, a plan was formulated to promote greater playground use. That included more shading to protect children and their carers from the hottest parts of the day, and the introduction of play infrastructure tailored to different age groups.

What followed, says Schuff, was transformational. “Within a week of these elements being installed and in the space of one hour, we counted over 60 different people, of which half were young children between zero and eight years old.”

Inclusivity, consultation, representation

Arguably, community-informed, multi-organisational approaches of this type are the exception, not the rule, with city decision-makers frequently operating in siloes.

Dr Shivani Gupta, Senior Inclusive Design Manager at Global Disability Innovation Hub, says this can render the best-intentioned projects ineffective. She describes an initiative in one city to introduce low-floor buses with wheelchair ramps, making climate-friendly public transport accessible to people of determination. “The pavements did not have a curb cut for the access ramp because that was the responsibility of a different department, so the buses were quite useless,” she says.

“Disability is often seen as sitting with one ministry or department,” she continues. But disability is a cross-cutting issue which needs to be addressed by every department, be that infrastructure, transport, education or climate change.”

Community consultation is also limited, with vulnerable groups such as people of determination lacking representation in municipal fact-finding processes, says Dr Gupta.

“I'm sure urban planners do invite participation,” she says, “but how meaningful is that participation? A lot of time, persons with disabilities may require additional support such as sign language interpretation and materials in alternate formats so they can acquaint themselves with the discussion points.”

Making the invisible visible

Community visibility is all about data, which is not always readily available. Dr Gupta points to a dearth of disaggregated data on the urban needs and experiences of people of determination. Yet when those information gaps are filled, the results are impactful.

Ahmad Rifal, Executive Director of Kota Kita Foundation, describes an initiative aimed at shedding light on the experiences of people of determination in Banjarmasin, Borneo. Through a survey conducted in association with UNESCO, the foundation identified 2,500 previously “unseen” people of determination, 75 per cent of whom never traveled outside of their homes due to a lack of accessible infrastructure. Community consultation followed, which resulted in an inclusive design project for five accessible public spaces. Their success, Rifal says, “exemplifes the positive impact of participatory approaches and community engagement in creating public spaces that are not only functional but also deeply meaningful to the people they serve.”

On the technology side, Oliver Kraft, Executive Vice President for Sustainable Communities at Siemens Smart Infrastructure, highlights the ability of Internet of Things technology to learn from people’s movements and activities in their homes, with those patterns then reflected in more efficient energy and water use, which, by extension is more cost-effective for households.

“The true value of the internet of things is that you provide visibility,” says Kraft. “That then allows businesses, city dwellers, and government to take smarter, more sustainable decisions on a day-to-day basis.”

The power of participation

In addition to community representation, leveraging human skills and resources and providing economic opportunity can feed directly into helping cities build climate resilience.

Ghaith Tibi, Associate Urban Planner and Middle East Sustainability Leader at Arup, highlights the value of tapping into local expertise.

“In response to climate extremes, many communities in the global south have developed adaptive architectural designs and building techniques suited to their local environments,” he says, adding that such techniques might even inspire sustainable design approaches in cities of the global north.

Kenya’s coastal communities, for example, still build with locally available and adaptive materials such as rammed earth. This contrasts with the shimmering glass skyscrapers that dominate the capital, Nairobi’s, skyline and which, by trapping rather than reflecting sunlight, contribute to the urban heat island effect.

Also in Kenya, inhabitants of informal settlements are being given opportunities to join the formal economy and contribute to their cities’ climate resilience. Through the Building Climate Resilience for the Urban Poor programme, led by Kenya and Brazil, the aim is to identify residents of marginalised neighbourhoods who are already acting as community waste managers and segregators and offer them salaried roles.

As Nasra Nanda, CEO of Kenya Green Building Society, points out: “These are already ‘green’ jobs.” By widening the net and capturing overlooked expertise, she suggests, the socio-economic potential is considerable. “More than two million of Nairobi’s population reside in informal settlements. That could easily equate to a million jobs.”

Cities should also acknowledge the power of social and cultural norms, says Ghaith Tibi. “Communities in the global south often exhibit strong social cohesion and resilience in the face of adversity. Leveraging community networks and indigenous practices can help build resilience in cities across both the global north and south.”

This is reiterated by Dr Charles Konyango, Kenya’s National Director of Urban Development. “Often during a climate disaster by the time government [agencies] reach the site, the community will have mobilised huge capital, including human resource, food and shelter.”

Funding: a two-way street

Urban interventions for people and planet need capital. This too should be subject to community engagement, according to Jagan Shah, CEO of The Infravision Foundation. “Local governments must be accountable to their citizens and citizens must be aware of how the city affects their individual and societal goals.”

Community participation, he adds, should be a precondition of funding. “Impact funds are an effective way to approach the development of urban infrastructure and services. The ‘performance for results’ paradigm promoted by the World Bank can become the mantra for sub-national governance and finance for urban development.”

To give the last word to Charles Landry, author, Chair of the BMW Foundation RISE Cities Sounding Board and Co-founder of the Creative Bureaucracy Festival, it’s time to reimagine what we mean by value. “If projects are merely assessed in terms of financial return and exclude potentially negative social, creative, heritage or other impacts, those are then bad projects.”

Jagan Shah suggests that community participation should be a prerequisite for urban investment

SUSTAINABLE CITIES IN ACTION FORUM

From 5 - 6 March 2024, more than 400 urban leaders and experts gathered at The Nexus, Expo City Dubai, for the inaugural Sustainable Cities in Action Forum. During a packed programme of dynamic panel discussions and cutting-edge workshops, delegates from all walks of life explored actionable solutions for catalysing urban development across the Middle East, Africa and South Asia.

We'd love to connect with you

For general enquiries, please fill out the contact form or send an email to impact@expodubaigroup.ae